Day 4 (Dawn of the Dark Age)

The Order of the Hammer (or, colloquially, the

Hammerites) doesn't mess around. Basically, imagine if the

Cathars had teamed up with the

Templars to overthrow the Vatican, and you pretty much have a flavor for the

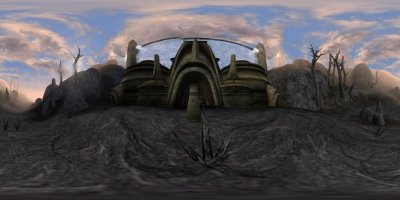

Hammerites. Their zeal is tempered by an obsession with their own imperfection, which they seek to purge through the construction of bigger and better structures. This cathedral is one such example.

The

Hammerites worship "the Builder," a faceless being whose entire persona is captured by Genesis 1: he built everything perfectly. Ironically, the

Hammerites are blind to the central paradox of their religion: if the Builder's creation of the universe was without flaw, how is it that humans (and, byextension , human nature) have imperfections? The blame is generally laid at the feet of the Builder's metaphysical nemesis, the Trickster, but this basic question (how can a good/perfect being be responsible for the creation of evil/imperfection?) is a core challenge to monotheism.

Hammerites are stark dualists with the reverse view of the heretical

Cathars. They view the spirit as fundamentally weak, and take their strength from the physical. The Trickster represents temptation and impulse, both mental weaknesses. So they seek to purge the spirit and leave behind the pure perfection of the Builder's creation: the flesh. And they have the muscle and the stonework to back it up. The Trickster's worshippers (the so-called "Pagans") are generally on the run from

Hammerite justice.

In the City's dark moral landscape, they're no better or worse than the other faiths available. Though the

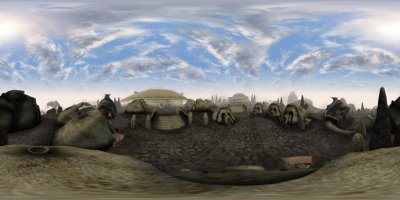

Hammerites are intolerant, insular, and belligerent, they live up to their promises. They protect their own with paramilitary enthusiasm, mete out harsh but consistent justice, and seek to improve the public good through their works. The overall flavor of the city (industrial) tends to suggest that the

Hammerites are waging a winning battle against the forces of "naturalism."

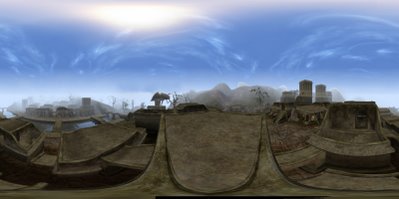

But for all the architecture they've built, it's very unclear whether they will survive in the long term. The Metal Age was brought about by a disastrous schism in the

Hammerite ranks (a theological divide over whether man had the authority to build automatons in his own image), and the dawn of the Dark Age finds the

Hammerites weakened and withdrawn. The

Hammerites are forcefully dogmatic, but their architecture is pleasingly neutral, and will no doubt continue to be used even if their religion collapses or fades away.

We have no real sense of what drove the construction of the cathedrals that dot Europe. Their construction took centuries, at enormous cost. Ignoring for a moment what that meant to city leaders and church officials, what did it mean to the common man? Did he look up at the colossus in his city square in wonder, or with the jaded gaze of someone who has seen it their whole life?

Will the Builder's message be somehow conveyed by these stones? Or will they, given time, lose that metaphor and simply become stones?