The City, First City Bank And Trust

Day 5 (The Metal Age)

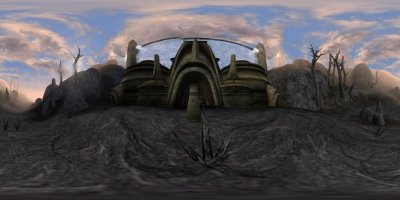

Before me is the target in the single most intense heist experience of my life. A virtual experience, admittedly, but a memorable one nonetheless.

I've spoken to others who have visited the City and partaken of the criminal recreation it affords, and most speak of the First City Band And Trust (FCB&T). Some speak of it fondly, others with clear frustration. I speak with little doubt when I assert that the FCB&T is a masterpiece of worldbuilding on a small scale. Rather than the more common tasks of building a town or a dungeon, FCB&T is a single building, believably executed and constructed with a dedicated purpose: security.

FCB&T is not the largest target The Metal Age has to offer, but its small size is part of what makes it difficult. Unlike some of the larger targets later explored, the bank itself isn't larger than it needs to be, which means that a thief is almost always within earshot of a guard. A short (say, 25-foot) hallway can become a laborious challenge when composed entirely of resonant marble that tends to echo every footstep.

The objective is nothing short of access to the bank's central vault, a tricky operation requiring unlocking the vault, raiding the records archive, and finally weaving a very cautious path through a tight web of human and mechanical security. Normally, a job of this kind is executed by a team, but in The City, it's always a solo mission. Both in terms of margin for error and mission time, this mission is among the most challenging to do well in the broad scope of virtual criminality.

A common problem in modern world-building of this type (i.e. the stealth-oriented variety) is mission linearity. The Adventures of Sam Fisher, for example, are basically a Family-Circus-style "follow the dotted line" game that requires picking one's way along a specific path that is usually the *only* effective path. Consequently, each encounter can be treated as a single puzzle, to be ignored once it has been conquered. This is, I believe, a major flaw, in that it panders to an uncreative audience.

FCB&T represents the opposed (and, I believe "true") path of stealth adventure: freedom. The building has at least three possible means of entry, which vary considerably in their difficulty and risk. Since the building is realistically designed, the entire structure is accessible internally, but the tightness of security turns a normally efficient layout into a shifting labyrinth of mobile, attentive threats. It is up to the thief to (a) plot a way in (b) plot a way out, and (c) determine how best to navigate internally between the various objectives. This active planning on the part of the visitor (rather than on the part of the world's designer) is the key to "freedom" because it places the entire burden of how to accomplish the objective on the visitor, rather than laying things out in a line.

This kind of freedom is a rare experience. Most virtual worlds suffer because of their simplicity. Giving a single structure the level of complexity seen in FCB&T is harder than building an entire town if the buildings are just empty boxes.