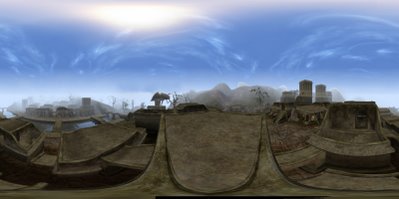

Vvardenfell, Ald'ruhn

Day 14 (Year 427 of the Third Age)

There's something deeply unsettling about a fortress built from the dead and manned by the doomed.

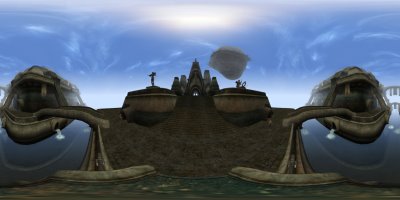

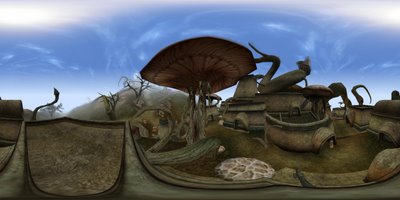

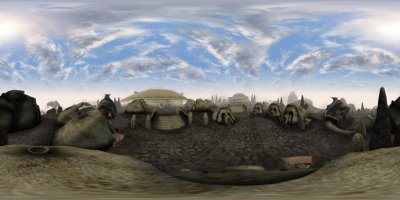

Ald'ruhn is the center of power of House Redoran, stoics who believe themselves to be the defenders of the good folk of Morrowind from corruption within and without. To the left, the massive fortress of Redoran looms. It is, I am told, the carapass of an improbably large crab-like creature known in myth as Skar. In essence, they have hunkered down inside the skeleton of a beast, anticipating a war at any time.

The other buildings imitate its organic style, leading to Morrowind's most distinctive style of architecture. As a city, it is striking on the rare days that the sky is clear. Normally choked by silt fromMorrowind's central volcano, the city's full glory was revealed by today's strong wind from the west. Within the hour, the wind is expected to weaken, and the storm to resume.

Redoran's politics are very much those of a house under siege. As stubborn nationalists with a militaristic tradition, they see enemies everywhere. In a way, they are right: at the time of my visit, a war is being waged in the shadows between religious conservatives and a hidden cult of heretics (sometimes called the Sixth House or HouseDagoth). But most who pledge to House Redoran believe in their threat whether it exists or not. Soon (chronologically, some months from now), the Sixth House will fall, and it won't have any effect on HouseRedoran.

This is because belief in a threat is often a more powerful force than the threat itself. After peace with the Empire and the destruction of the Sixth House,Redoran will remain vigilant, anticipating another attack "any day now." This vigilance, while commendable, has nothing to do with reality. Redoran will man the walls as long as it stands at a House, because it is certain that it will come under threat.

Here's a secret: they're right. In just seven years, this city will be totally destroyed.

Being a tourist on the New Periphery is sometimes disorienting because you not only hop between worlds, but back and forth in time within a world. And past visits to this world's future revealedAld'ruhn's doom to me. Daedra will swarm from another plane of existence to attack mortal holdings, and the great shell of Skar will be sundered. As someone free of the constraints of this world, I am also powerless to stop it. It has, in a sense, already happened.

Imagine being in Stalingrad (now Volgograd) in 1935, and knowing it would be the site of the costliest battle in human history (well over 1.5 million casualties, eight times the loss of life caused byWWII's atomic bombs). Imagine knowing you couldn't stop it. We are lucky, as humans, not to have the kind of foreknowledge. Because the lesson of HouseRedoran is this: given enough time, there will *always* be conflict. Perhaps not a war, and perhaps not within your lifetime, but some day.

I don't hold Redoran's surliness against them. Their duty is driven by enormous grief of knowing that war is coming. They know that, one day, they or theirdescendants will die defending this city. They know this as a matter of faith. If it weren't true, it would make them zealots. Knowing that it is true, it's difficult for me to see them as anything but tragic heroes.